Am I alone in wondering what’s going on in the heads of babies and toddlers and even first graders? Clearly there’s some weird cognitive “stuff” percolating in those little noggins.

What exactly do I mean? Well, if you give a crayon to a toddler named Martha, or even Suzanne, and point her toward a clean white wall, she’ll likely draw something like this:

Which is just a scribble, right? But … does Martha look at it and think “Wow, I’ve really captured the inner beauty of my mom in that portrait.” Do they “see” it as something more than a scribble?

Add a little bit of maturity and the question grows even muddier. Because now there’s a bit of fine motor control that allows for some more precise drawing and yet when Bobby draws a cat it’ll look like this:

Definitely more than just scribbling going on but still … not the most convincing cat in the world..

Weird, right? At this age you’d think they see what WE see and thus they’d look at their picture and go “Whoa, that’s terrible! What was I thinking? That looks nothing like Mr. Frisky. I’m giving up on art and going into banking. That’s where the money is, anyway.”

Yet they don’t. When I ask Bobby what those strange tentacles are he says “his feet”. Clearly old Bobby knows what he’s drawing and yet … surely Mr. Frisky’s feet don’t truly look like that to him.

You can, if you’re sitting with Bobby, gently indicate how a cat might really look and it will have zero impact. I know - I’ve tried. Box with tentacles will remain “cat” in Bobby’s opinion, regardless of my external artistic input.

And then, give it another year or so of development and when you ask Bobby for a tiger he’ll give you this:

So strange, right? When does the changeover in perception occur?

The reason I mentioned “even first graders” at the start of this Letter was because of a personal observation I made in that very grade. I was in an art class (yes, this was so long ago that art classes still existed in grade school …) and we were all drawing on paper (no finger painting that day). My desire was to draw a station wagon and although I don’t have the actual drawing any more I do recall it. It was pretty reasonably accurate, although I hadn’t used a ruler and I internally acknowledged to myself that the car sagged in the middle.

Why is this example of any interest? Because I recall looking at what my colleagues in crime were drawing and they were basically variants of the “cat” shown above. Just crude, largely unrecognizable collections of lines. And I remember wondering “Why are they doing that and not actually drawing the objects the way they look?”

For whatever reason, my young brain had made the leap from Blobby McScribbly to reasonably accurate representation before my classmates had and it was a mystery to me then and to me now what was going on in their minds.

I guess it’s this sort of thing that helped those Greek philosophers while away the hours between orgies (or were those the Romans …?). The tension between what IS and what is perceived.

That question is one that can strongly influence one’s own art, did you know that? Consider someone painting a scene and there’s something in the background. And because of distance or lack of contrast or whatever, the artist has no idea what it is. One approach that some will use is to try and figure out what the thing actually is, because once they know what it is they can use their imagination to help paint it accurately, using their predetermined knowledge to fill in the information gaps that their eyes are failing to provide. Maybe it’s a truck, seen edgewise, with a bush in front. Knowing that means you can sketch out what you know trucks look like and then make a bushy bush in front as well. They will be “correct”. Or … will they?

The other approach (and in my mind the correct approach) is to draw what you actually see. It doesn’t matter if you know what the thing is. The colors and shadows are what they are and you can simply put those down on the canvas. You SEE it and it doesn’t matter if you know what it IS, all you’re doing as an artist is painting what’s in front of you.

It may seem like an unimportant difference but it’s not. It really hearkens back to Bobby and his cats and hints at what it means to be “art” and not just a photograph (ignoring art photography for the moment). Artists can certainly pursue hyper-realism and so a great job of producing something that “looks real”. But they can also ask themselves what they see when they look deeper and produce something that doesn’t look exactly like anything “in the real world” but that nonetheless touches our emotions and understanding in a way that a photographically real piece wouldn’t.

Here’s an example. Consider a painting I did of my little Lord Barkalot:

What was I going for? Something that looked like the little pooch. A painted photograph, if you will. And here’s a second portrait of the barker supreme:

No question which is the more realistic, eh? But which is the more emotive? Well, I’ll let you decide and tell me in the comments.

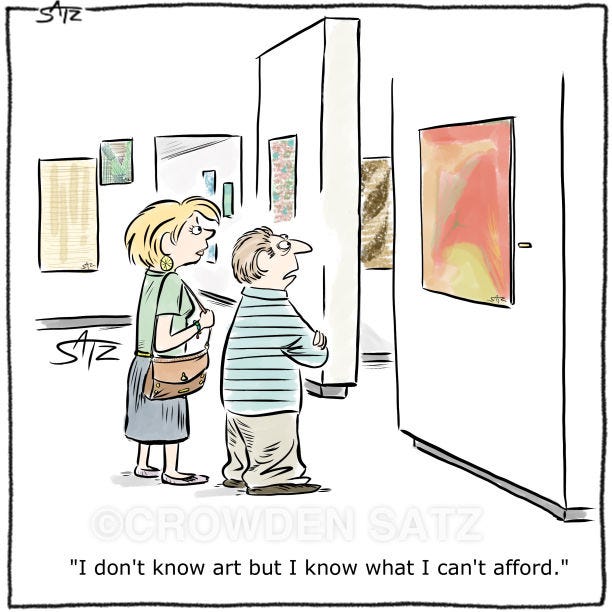

This is why we all seek out and relate to art. It’s just some pigments on a page or pixels on a screen, yet it moves us in ways that transcend the medium. Perhaps best explained by the following:

And now - some Nicky!

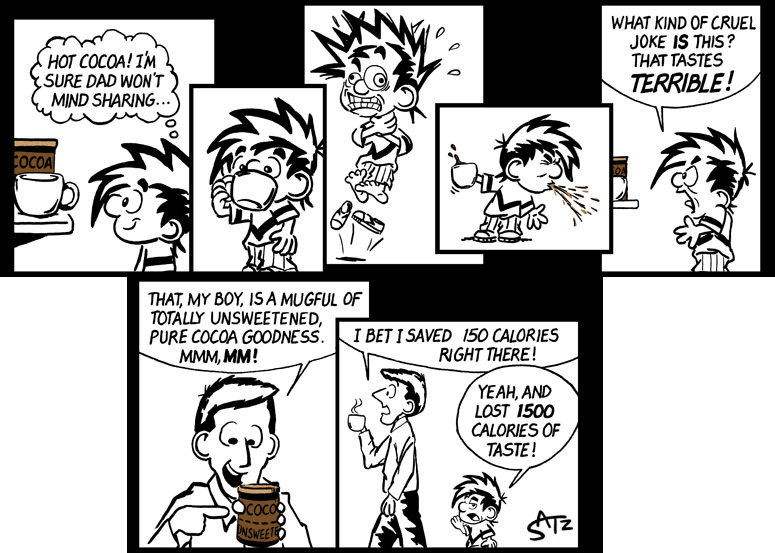

Nickyitis

Ah, good old C12H22O11. Sucrose! Something that we at Chez Satz do try to minimize. It takes a few cups but eventually just unsweetened cocoa and milk, or at milk in our case, tastes totally normal and the hot cocoa you’ll get served in a restaurant is undrinkably sweet.

Just another useful life hack, brought to you by your humble cartoonist. Do any of you do something similar?

As always, please feel free to share the goodness with your pals!:

Enjoyable and thought-provoking, as usual, Crowden. I like both the drawings for different reasons. Lord Barkalot looks more lovable in the first and slightly frightening in the second—perhaps it’s the purple or the abstract nature of the latter piece. Both reflect the artist as much as the subject. You were obviously an artist from the beginning—or cartoonist, but then they’re the same, aren’t they?